[Please scroll down for the mp3]

Women and children in early Victorian mines

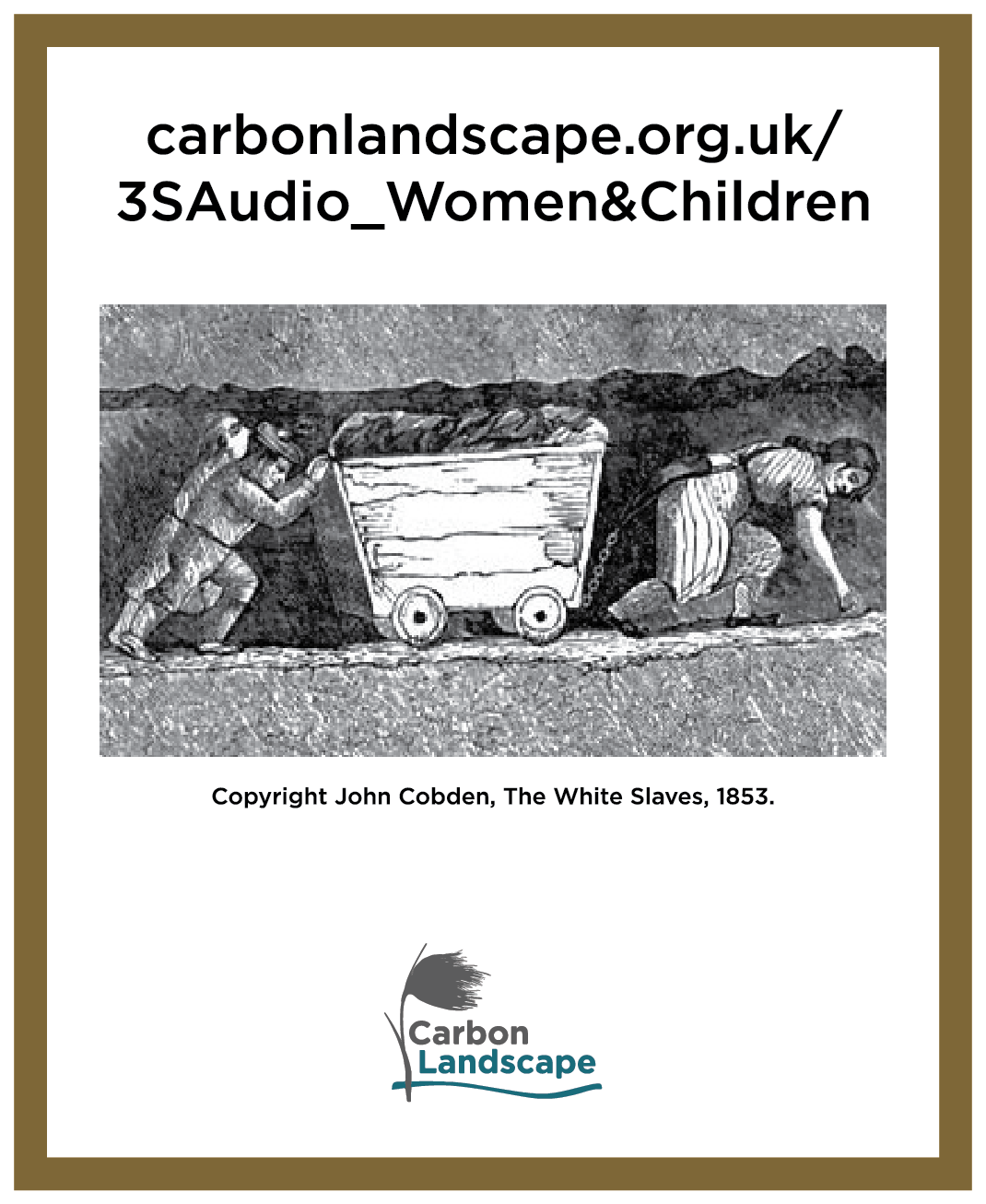

This re-enactment describes scenes of women and children being mistreated as was common in early Victorian times. Some listeners may find the audio upsetting. Betty Harris, from Lancashire Coalfields, gave testimony to the Royal Commission of 1842. What she, and other women who were working in the mines, said shocked a Victorian England and led to women and children under ten no longer working down the mine. Drawers were people who pulled tubs of coal to the pit eye where there would be lifts to take to the pit surface. They spent long days working underground. They were referred to as the white slaves.

“I am Betty Harris and I am 37 years old. I was married at 23, and went into a colliery when I was married. I used to weave when about 12 years old; can neither read nor write. My [husband] has beaten me many a times for not being ready. I were not used to it at first, and he had little patience. I have known many a man beat his drawer. I have known men take liberties with the drawers, and some of the women have [babies and are not married].

I work for sometimes 7 shillings a week, sometimes not so much. I am a drawer, and work from six o’clock in the morning to six at night; stop about an hour at noon to eat my dinner; have bread and butter for dinner; I get no drink.

I have a belt round my waist, and a chain passing between my legs, and I go on my hands and feet. The road is very steep, and we have to hold by a rope; and when there is no rope, by anything we can catch hold of. There are six women and about six boys and girls in the pit I work in; it is very hard work for a woman. The pit is very wet where I work, and the water comes over our clog-tops always, and I have seen it up to my thighs. It rains in at the roof terribly. My clothes are wet through almost all day long. I never was ill in my life, but when I was lying in. My cousin looks after my children in the day time.

I am very tired when I get home at night; I fall asleep sometimes before I get washed. I am not so strong as I was, and cannot stand my work so well as I used to. I have drawn till I have skin [fall] off me. The belt and chain is worse when I was in the family way."

The children in early coal mines mostly pulled or pushed tubs laden with coal from the coal face to the pit eye or to the main levels where they were then pulled by ponies. The drawer pulled the tub and was harnessed by means of belt around the waist and a chain through the legs. When harnessed, and moving along on his hands and feet, the drawer dragged after him the loaded tub usually on rails. If he was not sufficiently strong he had a helper, rather younger than himself, and these latter children in Lancashire were called “thrutchers”. This is the re-enactment testimony of John Halliwell, who was an overseer, talking about punishments given to children down the mine. Pauper children who were extremely poor, lived off charity and once they were old enough they became bound as apprentices to the colliers. This is a terrible story of a ten-year-old who was beaten by eighteen others. He was hungry and so stole someone else’s lunch.

"I am John Halliwell and I am overseer of the pit. There are many cases of cruelty with pauper children. A boy had not brought his own dinner when down the pit, and being hungry it was supposed that he had stolen another boy’s dinner. For this he was punished in the following manner.

One of the biggest boys got the boy’s head between his legs and each boy, of which there were 18 of them, inflicted 12 strokes on the flesh of the rump. I never saw such a sight in my life. The doctor said the boy could not survive, however he did.

It came out in the inquiry that any boy who refused to give his strokes was to be served the same way himself. This was not an extraordinary case and the older men seemed to think it was perfectly right and justifiable. The boy who was very ill was just ten. I believe the boys were not properly supplied with food by their masters and there can be no doubt that they were neglected."